Jonathan Skinner

Extinction Songs—

for Bachman’s Warbler

Night and day I am sad and speechless

not able to sing to the degree deserved

by the glorious warbler who always returned—

mowed down as summer burnt my garden.

For all its worth my best song is nothing.

Our countryside no longer hears the notes

that in all weathers accompanied us.

I won’t let song overcome my weeping.

*

Adapted from a 1270 Old Occitan complaint (planh), “Quar nueg e jorn trist soi et esbahit,” written in memory of the mayor of Cividale del Friuli and set to music by an anonymous minstrel, found in a book binding. Click title for recording.

Fortz chausa es que tot lo major dan

effort crowned I ask you to gloom all orders

and edge your forest skills logged mice a guess

and soon study coastal plans ears pooled on

my covered leader haunts country here

scarcely carry all vast woods captured byways

Louisiana reach out rays dells angles

it’s much I’ve days out cows pale die cast man says

can’t eye strain motes away can tail’s yellow hear

bends endures core taught home’s cool spot suffers

eye volens rates say new a key fallen

voice mice arm us near fort turning a space

near each escort near bay isle done out a branch

poise voice now it’s key near landscape dell air

need careful and leaf lores a small try eyrie

tseew quest sea realm in voice treasure veer miss

catch ends the unique squeeze hears us fends guess

near key far and silky ease dig round house year

caveats flights and grand record veneer

homilies annoy eyes aspire hands a key on

raised knee princess Caicos briar lost hopes

parrot touch seeking logged dells observing

the fond guard her come false the price admires

nickel full gamboge tread dewy fallen free air

lure show face raise a courteous comes joy afresh

and key in lock remains wrong devout stress

bends you have her out Kore’s firm close ear

defers ghost flights aids us occurs chose her

Ay! sane ideals! fools get vespers down eye ray

verse deals verse some verified mayor says

pair though gnats liquid ups echoes chalice

and no gardens saying you’re all seeing fire

remember moss compass a net serves her

*

Homophonic translation of Michael Vereno’s performance of Gaucelm Faidit’s planh for Richard the Lionheart (ca 1199), “Fortz chausa es que tot lo major dan,” transposed with diction drawn from correspondence and publications about the extinct Bachman’s Warbler. Click title for recording.

after Guilhem de Peitieus

Since I need to sing a song

I’ll make a verse, of Bachman’s

Warbler, named by Audubon

Not seen since the last century

Tucking leaves inside her nest

Of woven cane, when did the last

Vermivora bachmanii breast

Warm her clutch of eggs with ease

One of the rarest Parulae

Was first painted by Maria

Martin who had the idea

To pose it on a strawberry

Her in-law discovered the bird

Hearing a new note he was first

To put the species into words

Having shot it out of a tree

He wrote his friend: the beautiful

Skin enclosed was an old female

Note the black legs, deeply forked tail

It had to be a new species

Audubon concurred but declined

To include Maria’s drawing

Her backgrounds he considered fine

His bird posed on her Franklinia

We often confused its black throat

With the Hooded’s patch if not shot

Or with Northern Parula’s notes

A bird spotted uncertainly

Common on Suwannee River

But rare in the swamps, our warbler’s

Nests were tricky to discover

And none found since the late thirties

Recent surveys of the Great I’On

Plantation found not even one

Of these gap-successional cane

Specialists, declared agencies

Tasked with delisting, overdue

To our songbird we bid adieu

Of ‘buzzy brushies’ we’re left two

This ecocide we can’t appease

And now I must sing what’s unheard

Extinction’s hard to vocalize

*

‘Contrafactum’ of Count of Poitiers Guillaume IX’s vers “Pos de chantar m'es pres talenz” (ca 1111), drawing its end words from a ‘word cloud’ of correspondence and publications about the extinct Bachman’s Warbler. Click title for recording.

The melody for this vers is a fragment from a play for St Agnes that has a rubric stating it uses the melody from a planctus by Guilhem de Peitieus (“Faciunt omnes simul planctum in sonu del comte de Peytieus”), for whom no other melodies or fragments are extant. The meter of the play text that follows matches that of this vers. As the text by Poitiers has four verses, there are likely two full and one partial musical phrases missing from this melody.

There are only two extant recordings of the Bachman’s Warbler (from 1954 in Virginia and 1959 in South Carolina) documenting two different songs. These songs have not been categorised, but it is likely that they are the ‘unaccented’ territorial songs, of which there probably existed a great variety, especially as this warbler was observed (in prose accounts) to sing in flight and with a ventriloquial quality. The ‘accented’ advertisement song in all likelihood was never recorded. — JS

Click here for the Bachman’s Warbler (Vermivora bachmanii) recordings.

Further Information About These Texts

“Planh”:

The Old Occitan text (p. 132): https://issuu.com/elvanden/docs/a_399_booklet_digitale

The performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-L_aOf8amU

The melody: http://www.troubadourmelodies.org/melodies/461206a

The manuscript: https://www.librideipatriarchi.it/en/books/anonymous-planh-en-mort-den-joan-de-cucanh/

The recording: https://soundcloud.com/ecopoetics/planh

“Fortz chausa es que tot lo major dan”:

The Old Occitan text: https://trobadors.iec.cat/veure_d.asp?id_obra=1870

The performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_BB_SV7zLY

The melody: https://www.troubadourmelodies.org/melodies/167022Eta

The manuscript: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Reg.lat.1659

The recording: https://soundcloud.com/ecopoetics/fortz-chausa-es

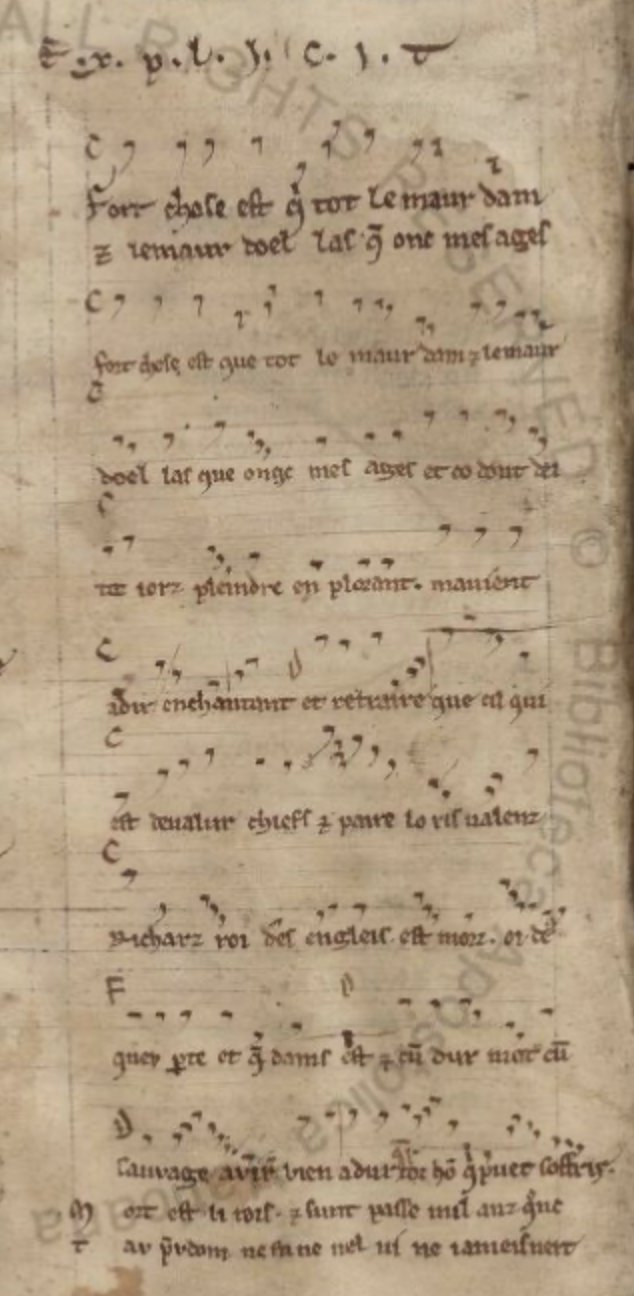

“Song of Extinction” (“Pos de chantar m’es pres talenz”):

The Old Occitan text: https://trobadors.iec.cat/veure_d.asp?id_obra=2256

The performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HFgILeqIRug

The melody: https://www.troubadourmelodies.org/melodies/183010

The manuscript: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Chig.C.V.151

The recording: https://soundcloud.com/ecopoetics/song-of-extinction

Notes on the Cessation of Song—

Poetry Mourning a “Delisted” Species

In 2023 I was invited to join, as a poet, a group of artists “holding space” with 21 species recently “delisted” or removed from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife by the US Fish & Wildlife Service “due to extinction” (as proposed by the latest, 2022 “five-year status review” and confirmed in October 2023), a project called Delisted 2023 and initiated by interdisciplinary writer and attorney Jennifer Calkins.

I chose Vermivora bachmanii, the Bachman’s Warbler, a member of the New World Warbler or wood-warbler family ‘discovered’ in 1832 and last seen at some point between 1958-1961 (last confirmed sighting) and 1988, the date of the last disputed record. Thought to be a “bamboo specialist,” the warbler bred in blackberry and cane thickets of disturbed and drier portions of US bottomland forest and headwater swamps in the Southeast and southern Midwest, with a breeding population possibly centered on the Mississippi alluvial valley (the species is also known to have bred on the Atlantic coastal plain near Charleston). The warbler wintered in a variety of habitats in Cuba, possibly associated with the majaguales plantations of the Hibiscus elatus or “blue mahoe.”

In 1833 John James Audubon named Vermivora Bachmanii after his friend John Bachman, a Charleston minister and naturalist, when Audubon painted the warbler onto a Franklinia branch drawn by Bachman’s sister-in-law (and later second wife) Maria Martin. Bachman had sent Audubon some skins of what he had surmised was a species new to ornithology. Martin would go on to paint many of the backgrounds for Audubon’s Birds of America, work that she was prominently credited for, unlike other collaborators on the volumes. The Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha) has been extinct in the wild since the early 19th century. Audubon never saw the Bachman’s warbler himself—he painted his likeness from the preserved skin sent to him by Bachman. As Audubon’s editor for Library of America put it: “Audubon’s old plate, showing warblers he’d never seen, sitting on a tree erased from nature, assumes new and urgent significance” (Christopher Irmscher, “With Bachman’s warbler and others added to the ‘extinct’ list, we must support biodiversity agreements,” Mongabay: News and Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline, 20 October 2021).

Until I looked more closely at Bachman and Audubon’s correspondence and read Martin’s biography I was not aware of the fact that Martin painted the warbler before Audubon painted and called it Bachman’s (see top image above). Bachman sent Audubon Martin’s painting along with the warbler skins, hoping it might be included in Birds of America and that Martin might be invited to paint other birds, but with the caveat: “if Maria’s drawing does not suit you, you may draw it over.” Audubon took her botanical work instead. (See Debra J. Lindsay, Maria Martin’s World: Art and Science, Faith and Family in Audubon’s America, University of Alabama Press, 2018, pp. 56-60; and Ruthven Deane, “Some Letters of Bachman to Audubon,” The Auk 46, 177-185, 1929.)

Investigating Audubon’s painting of the Bachman’s Warbler also leads us to the fact that slaves most likely helped to prepare the skins sent to Audubon, as well as labored in the background of the production of Birds of America, while Audubon used the slave-holding Bachman household in Charleston as a base of operations for his Florida expeditions. More generally, Audubon’s own slave-holding history, racism and desecration of Native American burial sites has prompted frank conversations about his legacy. Several Audubon Society chapters (including those in Chicago, Detriot, Madison, Portland and San Francisco) have already unlinked from his name, aligning with “Bird Alliance” instead. Along the same lines and for related reasons, the American Ornithological Society has announced that it will now change the English names of species named after people, beginning with 70-80 bird species in the U.S. and Canada. This is all good, well and thoughtfully done. But changing names does not change the facts with which, and at times against which, history is made and remade. Toppling settler-colonial statues, including those embedded in bird names, is a necessary first step toward biotariat solidarity. It would be a mistake, however, to disentangle species from the human histories with which they are, and have been, entangled. To simply erase erasure only perpetuates the erasures of an ongoing process of capitalist enclosure—techno-scientific, rationalist, divorced from culture, history and politics. There is a lot more to weep about than ‘just’ the extinction of a small songbird species.

The Bachman’s Warbler, “a bird of gaps, edges, and early-mid successional habitats within the general forest mosaic,” is “part of a trinity of three very closely-allied[,] buzzy-voiced[,] brush-loving species of Vermivora (‘buzzy brushies’), the other two being the Blue-winged and Golden-winged Warblers. These three birds are quite similar in size, structure, voice, and apparently habitat preferences as well” (Bill Pulliam, “Phantom Followup: Bachman’s Warbler,” Notes from the Soggy Bottom). It was even postulated that Bachman’s Warbler (or whatever we will call the bird, if we are also to rename extinct species) was not a separate species but a hybrid of the Blue-winged and Golden-winged warblers. A recent genomic study has confirmed what naturalists familiar with the species assumed, that Bachman’s Warbler was indeed a reproductively isolated species (“Genomes of the extinct Bachman’s warbler show high divergence and no evidence of admixture with other extant Vermivora warblers,” Andrew W. Wood et al., Current Biology 33, 2823–2829, July 10, 2023). Another relatively recent genomic study also has confirmed that Blue-winged and Golden-winged Warblers, known to hybridize as “Brewster’s” and “Lawrence’s” warblers, share 99.97% of their genes, with a pair of recessive alleles controlling the black throat patch, comparable to the difference between humans with and without freckles—in hybridizing, they may be evolving their own path away from the Bachman’s Warbler’s fate (“Plumage Genes and Little Else Distinguish the Genomes of Hybridizing Warblers,” David P.L. Toews et al., Current Biology 26, 2313-2318, September 12, 2016). Ornithologists and amateur birders in the field searching for Bachman’s Warbler also have been misled by the close resemblance of its song to that of the Northern Parula.

As a poet, I am particularly concerned by songbird extinction in our time: “‘The Bachman’s warbler is the only songbird known to have recently gone extinct in North America,’ said David Toews, assistant professor of biology in the Penn State Eberly College of Science” (“Extinct warbler’s genome sequenced from museum specimens,” Eberly College of Science, Pennsylvania State University, 23 June 2023). Connections between birdsong and lyric poetry are as old as the art itself: more than simply a topos for troubadour poetry, the innovations of the Spring chorus provided formal models, as noted by Jacques Roubaud in his study of the Old Occitan canso, La Fleur Inverse: L’art des troubadours (“Préface,” p. 9, “Auzels,” pp. 271-74; Les Belles Lettres, 2009). Song itself may have driven speciation in the great radiation of the oscine suborder (“Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation,” F. Keith Barker et al., PNAS 101 (30) 11040-11045, July 19, 2004; “Using song playback experiments to measure species recognition between geographically isolated populations: A comparison with acoustic trait analyses,” Benjamin G. Freeman et al., The Auk 134, 857–870, September 13, 2017). Still, what does losing one tiny buzzy song mean for what Bernie Krause calls “The Great Animal Orchestra”? Not much, perhaps. But as pre-echo of an increasingly likely future soundscape, the disappearance of the Bachman’s Warbler warns of greater gaps and silences. And who are we to judge the greater from the lesser?

By the time of colonial contact, Bachman’s Warbler may have been in extation, having lost much of its winter habitat due to sea level rise since the last glaciation. (See Paul B. Hamel’s Bachman’s Warbler: A Species in Peril, the definitive resource on Bachman’s Warbler, p. 22. For “extation,” see Richard C. Banks, Science, New Series 191, 1217+ 1292, Mar. 26, 1976.) But as a specialist of disturbed swampy areas, of successional gaps and edges where its preferred plant associates could flourish, the extaille species possibly benefited from the activities of early settlers, both Indians and Europeans, who created suitable openings in the forest. Extinction may have been hastened by the colonial genocide of indigenous peoples whose landscape management practices, such as “cultural burning,” helped to generate favorable habitat for this already precarious species. (For cultural burning see Michael K. Steinberg, “The Importance of Cultural Ecological Landscapes to the Survival of the Bachman’s Warbler (Vermivora bachmanii) in the Southeastern United States,” Southeastern Geographer, Vol. 50, 272-282, Summer 2010). After Bachman’s encounter in 1832, there seem to have been no sightings for more than half a century—until a sudden flurry of records (“rediscovery”) around the turn of the century seemed to indicate a healthy population. Hamel (op cit.) speculates that “high-grade logging in which only merchantable timber was cut . . . served to create the moderate disturbance to the forest canopy under which Bachman's Warblers could flourish,” a brief window of respite before “the emphasis changed from logging to clearing and planting. . . . By 1920 much of what had been apparently ideal breeding habitat had been completely cleared and drained for agricultural purposes” (25-26). At the same time, large areas of the warbler’s wintering grounds in Cuba were destroyed for agriculture. It may be that a series of devastating hurricanes sweeping through the Caribbean in the 1930s helped push the species toward extinction (18-20).

The tantalizing here then gone again, willow-the-wisp extation of Vermivora bachmanii haunts me, as we encounter irruptions of species in the habitat crevices of an increasingly devastated, fragmented and disturbed world-system. The scientific post-mortem undermines confidence in other-than-human resilience amidst ‘super storms’ that are the new normal. (The 2016 State of North America’s Birds report includes 436 species—17 of them warblers, make that 16 sans Bachman’s—on its list of “species most at risk of extinction without significant conservation actions to reverse declines and reduce threats.” The IUCN Red List turns up 19 warbler species in the regions of North America, Caribbean and Mesoamerica beyond the relatively safe category of ‘Least Concern.’) Yet guilt or rage (even “love and rage”) feel brittle and ineffective, one dimensional. As does a single-minded emphasis on “climate crisis” and the associated “carbon emissions.” We could very well “keep 1.5 degrees alive” (in a miracle scenario, were that were still possible) while doing little to stem the anthropogenic mass extinction, an extinction of lifeways that the language of “species” and “human/non-human” has few words for. I am called to meditate on an extinction event, if not to mourn such loss aloud in the capacity of my profession as poet; I want to pursue this assignment as a way to investigate rather than to simply express Anthropocene grief and mourning. There’s nothing wrong with simple expressions of grief, but any approach to grieving the extinction of a species quickly gets complicated. Both “Anthropocene” and “mourning” might be placed in brackets here. As problematic responses to the colonial and capitalist violence of extraction-induced climate breakdown and environmental destruction, obscuring as much as they expose, perhaps these terms belong together.

Does “mourning” risk the climate fatalism that “business as usual” encourages, contributing to a discourse of “resilience” and “sustainability” that now pervades funding for interdisciplinary academic research? Or rather, in acknowledging the finality of loss, does such mourning sharpen the critical edge of our zeal to defend and protect habitat for “listed” (threatened, endangered, but not yet extinct) species? Whether we actually can “mourn” ecological loss (with the rituals and cultural-literary genres such as “elegy” that have attended anthropocentric loss), or just sit with our big unresolved grief, is a question with no obvious answer. “Anthropocene,” with all of its built-in obscenity, still offers a site for the widest array of contributions to the most vigorous and necessarily interdisciplinary debates regarding the climate crisis.

I’m learning a lot from conversations with Nicola Hamer, whose PhD work on “ecopoetic mourning” at the University of Warwick I co-supervise with Dr. Fabienne Viala: such mourning necessarily turns to the Caribbean and its “scarscapes,” Hamer argues (after Braithwaite), crucible of the extractive violence and plantation economy driving the modern world system at full tilt by the time Bachman shot Vermivora bachmanii from a tree. We mourn a bird as much a denizen of Cuba as of Louisiana or South Carolina. For the moment, interpreting the invitation to “hold space” as a poet with the Bachman’s Warbler as being asked, in a way, to assume the role of professional mourner, I take inspiration from conceptual artist Taryn Simon’s installation of ritual laments, An Occupation of Loss. I love how Simon frames her installation, which I experienced when it was performed in London in 2018. Here I quote at length from the artist’s website:

“In ‘An Occupation of Loss,’ professional mourners simultaneously broadcast their lamentations, enacting rituals of grief. Their sonic mourning is performed in recitations that include northern Albanian laments, which seek to excavate ‘uncried words’; Wayuu laments, which safeguard the soul’s passage to the Milky Way; Greek Epirotic laments, which bind the story of a life with its afterlife; and Yezidi laments, which map a topography of displacement and exile. Simon’s installation considers the anatomy of grief and the intricate systems we use to manage contingencies of fate and the uncertain universe.

“In the act of lament, discontent is publicly performed. The status of the lamenters as professionals—performing away and apart from their usual contexts—underscores the tension between authentic and staged emotion, memory and invention, spontaneity and script. ‘An Occupation of Loss’ investigates the intangible authority of these performers in negotiating the boundaries of grief: between the living and the dead, the past and the present, the performer and the viewer.

“The abstract space that grief generates is often marked by an absence of language. Individuals and communities pass through the unspeakable consequences of loss and can emerge transformed, redefined, reprogrammed. Results are unpredictable; the void opened up by loss can be filled by religion, nihilism, militancy, benevolence—or anything. ‘An Occupation of Loss’ observes the contradictory potential of this space and the mourners who guide it. The bereaved solicit the authority of professional mourners to occupy, negotiate, and shape their loss. The mourners control a psychological experience by directing and embodying the emotion of others. Despite this authority, the women and men who command this abstract terrain have often been marginalized by governments, economic systems, and orthodoxy.”

Unlike ‘climate stories,’ extinction songs offer a performance of a feeling. The emotion around the loss of a species, a familiar song, a habitat, is different from that of personal loss—and yet in both cases there is loss, a loss that “solastalgia,” like Freud’s “melancholia” (diagnosing an incapacity to mourn or act), can’t quite address. Rather than sadness or depression, the performance is bound to invoke, as Simon makes clear, the contradictory affect of something “authentic and scripted simultaneously” (“In Conversation,” Homi K. Bhabha and Taryn Simon, Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss, ed. Aliza Waters, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017, 20). (The enigma of the Bachman’s Warbler, whose scarce sightings always seem constructed out comparisons across minute differences with associated species, heightens this sense of mediation.) There is furthermore no consolation—the nature the elegiac poet would restore us to is precisely what is being mourned. Such mourning points to transformation, to an in-between state made explicit by loss, “the vulnerable, the unspeakable gray zone opened up by loss, death, or displacement,” to quote Simon again, “where individuals, populations, and even history can be transformed” (24).

In my first approach toward “occupying” species loss in poetry, I began working with, amongst other sources, the translations of recitations of grief and mourning recorded on the occasion of the London performance of Taryn Simon’s An Occupation of Loss and included in the booklet accompanying a vinyl edition of the recordings—I’ve posted some examples on my blog Fractal Enclosures. But within my own Western-cultural tradition and occupation as a poet, closer to hand if more distant in time, I recall the troubadour genre of the planh (planctus or complaint). Strictly speaking, the planh laments the death of a powerful person, a protector or, more intimately, a beloved, although we also find poems of exile or penitence that seem to border this zone of lamentation. Barring one or two exceptions (including the famous poem by Sordel parceling out his lord Blacatz’s heart), planh, of which only 45 have been identified out of 2,542 troubadour lyrics, are less prized in the Old Occitan lyric corpus than vers/cansos, satirical or polemical sirventes, or even the debate poems, tensos (Oriana Scarpati, “Mort es lo reis, morta es midons: Une étude sur les planhs en langue d’oc des XIIe et XIIIe siècles,” Revue des langues romanes 114 [2010]: 65-93). On a good day, no one likes a weepy poem.

But for multiple reasons the planh speaks to my occasion. To start with, built into the genre as one of its rhetorical motifs is a confrontation with the impossibility of song—one expressed by the first planh I’ve attempted, an adaptation of “Quar nueg e jorn trist soi et esbahit.” How does one sing what calls for, or might even be constituted by, the cessation of song? This problem is acute for a poetic tradition that closely associates lyric subjectivity (je) with playfulness (joc) and joy (joi) and all three with love (amors). In the absence of the associations that move it, rhyme finds nothing to, well, rhyme with. (That said, the earliest troubadour, Guilhem de Peitieus, confronts this problem from the outset with his “Song of Strictly Nothing.”) Good ecocritical attention has been paid to obsolescence of the elegy under the Anthropocene, as a classical genre for mourning based on pastoral consolation (see Margaret Ronda’s discussion of Juliana Spahr’s “impossible elegy” in Remainders: American Poetry at Nature’s End, Stanford University Press, 2018). Like most troubadour genres, the planh, for the vernacular culture of Old Occitan poetry, was elaborated outside of that classical tradition.

At the same time, the planh is an art language form that speaks to the artifice of the occasion. Indeed, Old Occitan poetic forms (as in Lisa Robertson’s recent explorations) remain a resource for poetries resistant to the secular, disenchanted, individualized psychoanalytic voice that persists in dominant representations of lyric poetry, silencing a wide spectrum of poetic exploration and expression. Certainly, the lyric has a lot to answer for. Perhaps these Old Occitan forms provide a support for lyric impulse ready to confront (open up, negate, invert) in and through lyric its various bankruptcies. How, for instance, to lament the extinction of a species while excavating the Anthropocene sedimentations entailed in the scientific construction of that species, to occupy and decolonize loss?

Thus my experiment: to invert the anthropocentrism of the planh, displacing the important man or beloved woman with a tiny songbird. Of course, I would love to compose a beautiful song that makes readers weep, but I’m suspicious of any easy passage to tears, preferring for now the awkwardness of these translations. Awkwardness keeps in earshot the one connection I am certain of, between Occitan planh and Vermivora bachmanii—vocal invention. Though ornithologists go back and forth on whether or not to call avian invention song or vocalization, song nearly always wins out. David Rothenberg makes a good case for engaging birds as musicians, drawing on a long tradition within his discipline, though I might be prepared to make as strong a case for engaging them as poets—in other words, neither case is entirely convincing.

The homophonic translation of Faidit’s “Fortz chausa es que tot lo major dan” makes me listen to Old Occitan (a language I can read, with some effort) the way I might listen to birdsong as a poet, in an awkward space for English sound patterns. The fact the troubadours also composed the melodies for their poems makes me ready to confront another awkwardness: I’ve never had the gift of song. I did learn to read music, and played the flute in high school band and later learned to play the recorder—a baroque Moeck flûte à bec still in my possession—so the next step is to learn to play these tunes.

There are some 341 extant troubadour melodies, including seven extant melodies of the planh genre, with four different versions of Gaucelm Faidit’s “Fortz chausa es que tot lo major dan,” so essentially we have four different planh (including two fragments) with extant melodies. The scholarship by which these melodies—for a long time transmitted orally before being committed to script—have been preserved and have come down to us over centuries through a palaeographic wilderness of scribal transcription, sifted and organized by the meticulous archival and philological work of medievalists and the transpositions of musicological interpreters, dazzles me. It uncannily mirrors ornithology’s mania for detail and systems of interpretation built on arrays of multiple and minute distinctions. Both birdsong and troubadour melodies furthermore suffer a comparable material precarity. When the chain of oral transmission is broken, we rely on the artifact—often fragmentary, partial, subject to the vicissitudes of the medium as well as the inevitable obsolescence of archival practices. The digital ‘cloud’ is now supposed to be our definitive solution for storage—and indeed the offerings of the digital humanities open up wondrous terrain for an amateur medievalist, enabling me to quickly locate photographs of the manuscript sources for the melodies of the poems I translated—but doesn’t such a solution only shift precarity to the planet, with the carbon cost of every click?

Will I also learn to play Vermivora bachmanii’s tune? I’m haunted by the fact that—for a species known to science for more than 125 years—we have only two recordings of the Bachman’s Warbler, six minutes’ worth in total documenting two different songs. Such a small data sample permits few conclusions, and yet Hamel (op cit.) lists twenty-eight different publications including discussion of, and speculation on, the species’ vocalisations, often remarked as similar to that of the Northern Parula, its “notes being given in the same key and with equal emphasis. . . . The voice, although neither loud nor musical, is penetrating” (William Brewster, “Notes on Bachman's Warbler (Helminthophila bachmani),” The Auk8, 149-157, April, 1891). Warbler field guides until recently included phantom entries on the “probably extinct” Bachman’s Warbler with dutiful yet speculative sections on “Voice”: “Rapid series of buzzy notes, sometimes ending with a sharp slurred note: bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz-zip. Songs contain 6-25 bzz notes, delivered at a rate of 5-10 per second” (A Field Guide to Warblers of North America, Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett, Peterson Field Guide Series, 1997, p. 118); or, “First-Category Songs: monotone series of buzzes, sometimes ending in a complex whistled note” (Nathan Pieplow, Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of North America, 2017, p. 394). The best discussion I have found, on the late Bill Pulliam’s blog, considers recordings and spectrographs of the Bachman’s Warbler song alongside those of the other ‘buzzy brushies’ (Golden-winged and Blue-winged Warblers) as well as of the Northern Parula, comparing the different versions of these birds’ “dry thin buzzy . . . flat, staccato series of buzzy notes” (Bill Pulliam, “Phantom Followup: Bachman’s Warbler,” Notes from the Soggy Bottom). Princeton University Press’s authoritative Warbler Guide, by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle (2013), makes no mention of the Bachman’s Warbler.

This overdetermination of the mute artifact echoes the rather astonishing way in which the music of Guilhem de Peitieus’s “Pos de chantar m’es pres talenz,” one of the more celebrated troubadour vers (a favorite of Paul Blackburn’s, also, more recently, translated by Lisa Robertson, and performed by many medieval music ensembles) has come down to us from a small fragment of musical notation, just a few notes. The manuscript detail illustrating my translation shows all twenty of the notes—only indicating a short series of pitches over eleven words, without duration or other notation. The tune was found in a 14th century manuscript from Languedoc—as a fragment of music for a play for St Agnes with a rubric stating that it uses the melody from a planctus by Guilhem de Peitieus (“Faciunt omnes simul planctum in sonu del comte de Peytieus”). The words below the melody fragment aren’t those of the poem but of the play, yet they match metrically. While the words continue on the manuscript verso (with a series of blank staves) the melody does not. It was a keen-eyed, sharp-eared scholar who connected the notation with “Pos de chantar m’es pres talenz.”

Though we don’t have even a complete melody, one can find numerous recordings of this vers based on the fragment. I’ve provided a link to a version by Brice Duisit, from his album Las Cansos del Coms de Peitieus, chosen for its simple arrangement and lack of elaboration, retaining the simple yet subtly modulated repetitions of the vers. Peitieus’s poem is not a planh according to Scarpati (op cit.), but the rubric in the St. Agnes manuscript refers to it as a planctus. Either way, “Pos de chantar m’es pres talenz” certainly is one of the more beautiful death poems in the Western tradition (prefiguring, with a much lighter touch, Villon’s “Testament”). For that reason I count it among versions of Old Occitan planh for which we have the melody and by which I am attempting these songs of extinction—here adapted as a contrafactum (different poem to the same tune) that rhymes some of the too brief history of Vermivora bachmanii.

—JS, written in Warwick, U.K., February 2-9, 2024