Chant de la Sirène

ISSUE 5, Fall 2025

On Tyranny:

Poetics & Protest Art

Susan M. Schultz, Photographer: “An Open State of Attention”

Our Featured Artist for Issue 3 is Susan M. Schultz, known professionally as a well-published U.S. poet and American poetry scholar, and also a Professor of English Emerita at the University of Hawai’i-Manoa. Schultz is also an accomplished Hawai’i-based American photographer. In this issue, we particularly recognize her achievement in the visual media of photography. Not only has Schultz over the year captured compelling, often humorous, scenes of citizen protests against the Trump Administration; and in this activity, she joins our journal’s crew of volunteer “citizen photographers” who’ve been visually documenting all year the American people’s resistance to tyranny across the land—and whose photos now run like scenes of the carnivalesque throughout these pages. But Schultz also has continued her more “abstract” photography practice, producing in recent months a series of amazingly inventive, alluring—if also sometimes tense and apprehensive—images.

These “abstract” photos, perhaps oddly, focus on the ordinary. But they reveal an “abstracted” transformation of everyday “found” objects, and undergo a process of revealing something new in that supposed “ordinary.” As a photographer, Schultz sees and “takes” object images in what appear to be accidental “sights”—which she usually discovers, or constructs, while making daily walks with the family dog. Through her inventive camera lens, she manages to transform the regular-seeming image of “known” things by “making them strange.” Everyday glimpses of the real-world objects appear surreal through her lens. Schultz’s photography captures of the play of angles upon objects through shadows and light, and/or the power of hidden color or unrecognized design as revealed in close-ups. This Abstraction Series, as we call it in this issue, makes art out of seemingly “regular things,” like parts of old cars or rusty machinery, screws in a torn wall, dirty metal grills, peeling paint or broken windows, or in the fanning-out vision of tree mosses moving across vivid patterns of bark. In essence, she brings the quotidian world back to us as exceptional. It becomes worth pausing over these “looks” upon reality—because the “look” itself is different, charged with a strange luminescence.

Schultz works like a visual bricoleur, re-using the seemingly uninteresting—or the broken or abject—materials at hand. She then turns these into something entirely else, fascinating to behold. Through her inventive perspective plays and technical photography experiments, she turns “sightings” that we might assume to be banal into startling, visually dramatic events: mini-masterpieces of vision worth re-seeing and contemplating further. Making the ordinary extraordinary, in the way that old Dutch painters of the still life brought out an exceptional sheen or gloss in images of flowers or fruit pieces or kitchen bowls through oil—what the French call la nature mort, with all the creepy implications of a beautiful but “dead nature” in that phrase—Schultz’s Abstract Series becomes part of her continuum of multiple art practices that partake in the surprise and the absurd in life. Her photographs work in tandem with her documentary poetry found within the pages of recent books, including Meditations (Wet Cement Press, 2023) and her Lilith Walks series (BlazeVox, 2022 & 2025). Her 2024 book I and Eucalyptus (Lavender Ink) actually couples her photography of eucalyptus-tree bark with her poems that verbally observe and discover it. (And this year the book was translated into Italian by Pina Piccolo & Maria Luisa Vezzali, re-published at Lavender Ink as Io ed Eucalipto).

Schultz does indeed find and use her visual-study materials while walking through her Hawai’ian neighborhoods with a camera and a medium-sized hound named Lilith, a dog now famous through her social media posts and her “Lilith Walk” prose poems (new ones appearing in this issue). Depth, deterioration, the closeup of “strange” details in and upon the apparent surfaces of everyday “things” seem removed from the supposed Real by an enchanted lens, transforming any regular look at such “things” by exploring them, de-contextualizing them, removing them, so to speak, from what we like to think is the “ordinary” vision of human experience. Schultz’s photography abstracts literally take a seemingly known “sight,” that which most viewers would ignore or overlook, and reinvests that “sight” with the power of a very different image and, hence, a more analytical spectator. She makes us look again at things we think we know, visually understand.. She makes us work as spectators. We are asked as spectators to consider the duality as well as the multiplicity imbedded in every object and every view.

Shultz does so in that way that Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky describes the process of literary art, in his well-regarded essay “Art as Technique” (1917)— which introduced that concept of “strangeness” (as an English word translated more or less from the Russian) to poetry and literary studies. Literally, it is the “strangeness” Shklyovsky conceptualizes that Schultz literally invokes in her photo abstracts. That “strangeness” makes us, her perceiver/spectator, do a kind of double take in our own acts of seeing her chosen objects changed, renewed, through the artistic medium.

To see and experience the“double-take” in her photos: one is, indeed, “startled” by what is revealed by “strangeness,” inherently, according to Shklovsky, a process of “de-contexualization.” Schultz also has a new on-going series of poems called “Startles” (one of which is published in this issue). Her “Startles” poems, like her photography abstracts, appear to reflect upon the unexpected or “startling” moments a perceiver undergoes in observing one’s currently lived life within our also-strange socio-political times. Those of us living in America certainly do find ourselves immersed within a new strangeness, although not the aesthetic kind.

Can that political strangeness—the feeling of being adrift and bereft—be made into an aesthetic?

Schultz’s abstract photos often contain a dark, often chiaroscuro effect. These might remind the viewer of a scene of trauma—perhapsthe trauma, the horror, we in the U.S. are experiencing, watching literally before our eyes (through various media outlets and device screens) the fascist moves on display by the Trump wrecking ball. We have been watching for months now as our nation, once founded upon then-idealistic yet untested principles of an Enlightenment representative government—to become a seeming democracy—appears to be unraveling. Seeing / being part of what we thought was a government based upon principles of equality and law now devolve into a tyrannical despotic state, one that bears no relation to those principles embedded in the U.S. Constitution, can feel damaging to many of us. Do these abstracts mimic that potential response in the political spectator?

We’ve watched as the current U.S. Supreme Court has upheld all too many of these Trump Administration aberrations of American foundational principles. We’ve watched as too many holding power, like the Republican leadership in Washington D.C., have encouraged this devolution of our cherished freedoms and protections. We have been literally been acting this year as eye-witnesses to the un-doing of our democracy. We certainly have witnessed the un-doing of the very real and steady progress made toward an authentic democracy—even if America had not quite gotten there. We've been watching as beliefs and rights created under Civil Rights and the 20th century Feminist movements have been stolen from us. Many of us feel shattered by what we see and feel as a result.

The enigmatic and often literally dark aspects of Schultz’s Abstract Series might recall some of these shattering effects for the viewer. But they are also for her, as an artist, small statements of freedom. Shultz writes in her own Artist Statement below that her “abstracts” reflect her own engagement in freedom and liberation—even while some images might reflect a given viewer’s experiential panic at the darkness interior to any “sights,” and their re-interpretation of the “known” as perhaps indefinitely “unknowable.”

I believe is that her Abstract Series as published in this issue embraces the core irony in any workof art—one that embraces lived experiences of both creator and perceiver no matter how complex and even contradictory. One on hand, Shultz’s photographs might embody a dread-filled visual universe of continuous change, fear of instability, of spectatorial unreliability. On the other, they might embody their own inner creative freedom, a liberation generated in art and spectatorship itself. A bit like the image of Blake’s “Tiger,” in its “fearful symmetry,” these photographs “exist” within a conceptual insistence upon art’s duality and innate paradoxes.

I have been in dialogue with Schultz about my interest in her photography abstracts, and (below) she talks about her photography practice in her own words.—LH

Susan M. Schultz

Abstraction & Tyranny

The receptionist at my dentist’s office admired my camera the other day; she expressed disappointment in her own photographs because they aren’t like the thing she photographed. The problem with a photograph, she came close to saying, is that it’s a photograph, not real life. I suggested she think of photographs as themselves, something different from real life. She liked that idea, which has taken me nearly my entire life to arrive at. I’ve come to think of photography as a form of estrangement from the real, at least when it’s not the record of a rally or a wedding. Photographs can never be wholes, so the question is which of the parts do you select to “take.” The closer you get to an ordinary object, the stranger it seems. It’s like reading Gertrude Stein’s ordinary words out loud until you feel stoned; they may be iterations and not repetitions, but they do affect the nervous system! So, once I started taking photographs rather than snapshots—this would have been in 2018, when I first got a smart phone—ordinary objects became koans to me. I was drawn to decay and to rust, and to a eucalyptus tree whose trails of sappy colors on its trunk reminded me of abstract expressionism. There’s a photograph of a yellow curb in the nearby cemetery, with a previous layer of red poking through, that’s so disorienting that the framer called to ask which side is up.

Laura Hinton [the editor of this journal] has taken some of my abstracts for her anti-tyranny issue. She told me that abstracts feel tyrannical to her, and I can understand that. They certainly do not brook interpretation or emotional response, at least not in the way that the photograph of a cute kid will do. (Put up a photo of a dog, and your instagram will light up with “likes.” Post an abstract, not so much.) They are like the stills of still photographs, actively passive.

Yet abstraction also opens up space. Barnett Newman’s “Stations of the Cross” at the Tate Modern in London seemed to fill my lungs, offer that often unattainable mental spaciousness Buddhists talk about and that I experience in my meditation practice. So “taking” these abstracts—taking photographs of regular objects that are transformed into abstraction by the camera lens—has become a relief for me as an artist from the incessant surreality of our politics.

The tyrant tells stories, simple ones. The tyrant tears down part of the White House to build a ballroom that will fill with chandeliers and gold. Albert Speer was architect of the monumental. Authoritarian art dares not bleed ambiguity or mystery. But a painted curb, once Hawai`i’s weather has worked on it and a photographer has “shot” it, becomes an open invitation to look beyond the rules (don’t park) and toward an open state of attention (look here!)

Table of Contents

Rae Armantrout, with art by Toni Simon

Susan M. Schultz, with her own abstract photographs

James Berger, with abstract photographs by Susan M. Schultz

Pam Ward, with son recording by Aldon L. Nielsen (after Bob Dylan)

K.T. McEneaney, with painting by Anne Webster Waters

Tony Medina, with paintings by Giacomo Cuttone

Steve Benson, with abstract photos by Susan M. Schultz

Shirley Geok-Lin Lim, with visual poems by Janet Kaplan

Scott Hightower, with postcard mail art by Bryant Webster Schultz

Carla Harryman, with video by Alexis Kravilovsky

Adeena Karasick & Warren Lehrer

Charles Bernstein & Uche Nduka, with paintings by Regan Good

Tenney Nathanson & James McCorkle

Bob Perelman & Burt J. Kimmelman

Margo Berdeshevsky

Scott C. Smith

Rick Burkhardt & Laurie Price

Pina Piccolo

Mark DuCharme & Norman Fischer

Eileen Tabios, with interview by Mark Louie Tabunan (Ilocos Sur)

Mark Scorggins & Jill Stengel

A.L. Nielsen

Cynthia Hogue & Karen Brennan

Jonathan Skinner

Sam Truitt & Kimber Truitt

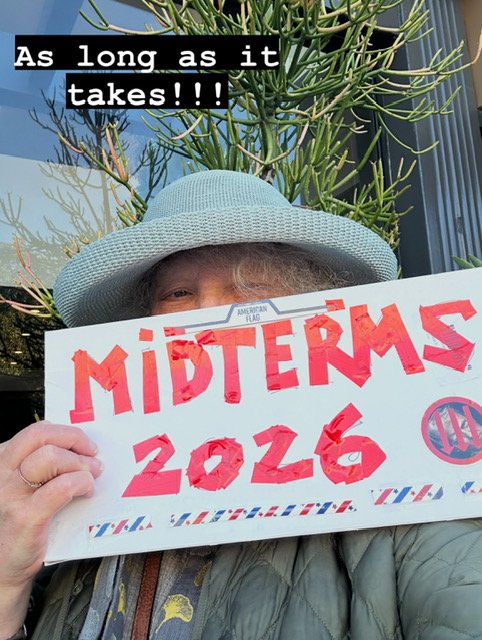

Citizen photographer

Susan Aberg

takes a protest selfie

Aberg emailed CDLS photographs frequently throughout the year from her protests on the streets of Berkeley, California (this photo was in her last email batch from a protest in November 2025).

Issue 5’s Citizen Photographers

With special gratitude to

Susan Aberg, Dean “Willy” Apperson, Abigail Child, Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Warren Lehrer, Cynthia Levinson, Joe Harrington, A.L. Nielsen, Pina Piccolo (dual Italian-U.S. citizen), Brad Richard, Susan M. Schultz, Toni Simon, Alan Sondheim, & Barrett Watten.

A warm thank you to this issue’s “citizen photographers,” those friends and colleagues and friends of friends and colleagues who responded to this journal’s call for snapshots of the anti-tyranny demonstrations happening across the United States throughout the year.

Photographic images by citizens of the citizens—those who took to American streets demanding basic American rights & the rule of law under the Trump Administration—have come in to us by email from California to New Orleans, Kansas City to New York City, from sea to shining sea.

These images flood our pages—and they bring us humor, joy and hope.

This issue is dedicated to the memory of four brilliant colleagues in poetry who have recently passed —

Tyrone Williams

Bernadette Mayer

Pierre Joris

Lou Rowan

Rest in poetry, dear friends.

Laura Hinton

Editor’s Introduction

On Tyranny, Resistance & Language (via Timothy Snyder)

The story told is that Timothy Snyder—then a Yale University scholar of 20th century European history and fascism—just jotted a few notes on a napkin. It was right after Donald J. Trump had won the 2016 election for president of the United States. How was he to warn his fellow citizens about how to act in the face of what he knew was to come? How could he use his scholarly knowledge of history and authoritarian take-overs in modern Europe to help his countrymen blunt a fascism represented and fostered by Trump’s overpowering political wave?

Snyder’s brief lines on a napkin turned into a social media post. Then, more posts. These posts were so popular that Synder used his considerable knowledge of Western fascism’s modern formations to add historical contexts and examples to his few words of advice. At some point he must have gone to a Word.doc and composed a text. Snyder’s napkin scratches would become a slender but potent volume, modestly entitled, On Tyranny: 20 Lessons from the 20th Century. It quickly became a bestseller, with over a million copies sold, and widely available for free on the internet.

So many of us seemed to see, even during that first election period, and then again during the early months of the first Trump presidency, the working out of a new playbook from the Third Reich. We saw the blustery behavior of strong man Mussolini-type. We saw him blaming certain groups—in this case, brown-skinned immigrants—for society’s ills. We saw the call to a new racialized white hegemony against these supposed “criminals” and “outsiders” to the white regime. We saw the behavior towards women, as acolytes to the man in power, as sexual objects and/ or domesticated controlled wives. We observed and criticized the sympathetic ties already on display between our new president and totalitarian dictators like Putin. We thought we saw it all.

As Snyder would write in the first sentence to his little book’s prologue:

“history does not repeat, but it does instruct.”

Yet how many of us in the U.S. did see the warning signs and act accordingly? How many Americans today do read about or even casually study history? How many U.S. residents can be prompted away from their social media posts and their on-line shopping sprees, or visits to Walmart and Home Depot shopping malls, to read even a wee little book? A wee terse little important book, one that summarizes how average folks can help combat fascism in society. How many?

A book as prophetic as the unlikeable Cassandra’s predictions, warning us what we don’t want to hear: this is Snyder’s book as first published in 2017. Underpinning its philosophy is that there is no such thing as American exceptionalism—that America, too, with its “checks and balances” between three branches of government, the same America with its brilliantly authored Constitution and an appendix called The Bill of Rights, the same America that has stood for about 250 years as the great democracy of the world, could be changed—seemingly overnight—by a real-estate salesman from Queens, one with a bent for absolute control over others, a toxic narcissist who, like any strong-man leader, believes a totalitarian society best fulfills his dreams and desires to rule over others—and to make himself rich.

If you haven’t yet read On Tyranny, a free pdf is available HERE. I highly recommend it. It is the basis of my conception of this journal issue, which has been on-going for about 11 months, or since Trump was inaugurated a second time to the office of the president.

And if you don’t have time to read this small but truly profound book about the crisis of our times in the U.S. and Europe—also seeing a wave of tyrannical political leaders rising up and winning popular elections—a pithy summary of Synder’s 20 points in On Tyranny is available HERE.

But—I hope you will read, or have read, his book. It is the basis of much of the anti-tyranny writing and art in these journal pages. Nearly 50 poets (many of them also scholars) and visual artists have allowed me to fill these on-line pages with their anti-tyranny work. A particular shoutout goes to the Anti-Tyranny Workshop I started as editor of an issue that did not yet exist last March, via Zoom. I got the idea from scholar and poet Jennifer Scapettoni, who went on to also start her own group. (I lost track of them when they went to the Signal app, but they were doing some mighty reading and articulated thinking.)

In our group, we gradually formed ourselves as about eight very different but committed-to-the-work poets, who show up with their Zoom faces across screens from Hawaii to Maine to France (where I was then working last winter, getting a breather from the on-going political horror and debacles going on in the U.S.). These members of our still on-going Anti-Tyranny Writing group all have generated new and inspiring work specifically for this issue of the journal—and we have supported each other as we built together a way to articulate—and not be afraid of—writing about what we see happening. Without this group, I don’t think the issue would have happened. I would have felt too isolated in my feelings of trepidation and a certain amount of horror. Along with what I call my troupe of Citizen Photographers—who I formal thank in a little area on the left to this Introduction, who sent me such great pictures of the now nearly-year long U.S. protests against tyranny—they kept my heart singing and alive during this labor-intensive and often terrifying project.

Our first act as an Anti-Tyranny writing collective was to read Snyder’s On Tyranny.

*

The patterns leading to the current rise in an American fascist state obviously did not evolve overnight. Rachel Maddow’s widely available and finely produced podcast, Ultra (first broadcast June 2024), and which she then published in book form later the same year, traces the development of a fascist coup inside some of America’s highest power institutions during the 1930s through ‘50s. This fascist movement emerged among a conservative Catholic Church clergy; it involved the media and the courts; and it circulated throughout the U.S. Congress, even using federal funds to mail propaganda. It expanded its subversive power during WWII when America was supposedly at war against the NAZIs and yet also supported an underground movement that cooperated with Hitler—within the U.S. government. This earlier 20th century American fascist movement culminated and then exploded with McCarthyism by midcentury. It seemed to wear itself out through the final shame of a blatant fascist ideology of a Joe McCarthy.

But of course, it now seems that U.S. fascism just went underground during that time. The streams are now bubbling over the ground and flooding us.

And we could also, again obviously, say that American colonialism and expansionism—the obliteration of the Native American population by European colonists, as well as American imperialism abroad (driven today more by lust for oil than land); of foreign-policy boo-boos like the Vietnam War, steered by anti-communist ideologues even after McCarthyism was dead—point to a strong current of fascist sentiment running throughout U.S. political history for centuries now.

And—again obviously—we could say that American slavery and its legacy in the on-going systemic racism in this country, as well as modern corporate class warfare vying the super-rich elites against working people, reveal a fascist underbelly to the American Dream.

Then we might add that a media-driven misogyny targetting the well-being of independent women, especially those who serve now in leadership roles, are all indication of the American fascist trend, which that has apparently co-existed while the country itself has risen into a global superpower known for its democratic system and values.

I must confess that I, myself,—educated and aware of these facts—was been shocked and depressed at the rise of Trump and his MAGA acolytes taking over all forms of political power in my native country. Call it the latest reappearance of American fascism. I should have been more prepared, more savvy. I remember when Trump first won the Republican nomination for president. We couldn’t believe it. We certainly couldn’t believe that a Donald Trump would win the presidency—against a candidate as informed and ready to lead as Hilary Rodham Clinton. (And there were a few problems with that candidacy, I won’t go into now. But blaming HRC on the corporate approach to political fundraising—when all the white men forever have been doing the same—was not helpful.)

The day before that election, November 2026, I was teaching as I had been for decades at my university in New York City. I remember purposely wearing a “pantsuit” to teach my college classes that day—the day before I thought we would be celebrating the election of the first female American to win the US presidency. I mean, how could she lose against a Trump? With everything that had already come to light about him.

OK, so I was feeling a little rocky after James Comey released his stupid statement about Hillary Clinton’s emails two weeks prior to the election. Yet somehow I was convinced that the American electorate was smart enough not to elect Trump.

And was I wrong. And I remember the day after the election, a teaching day again, and I was standing in my evening seminar graduate class room that Wednesday, and the seminar desk was filled by the women who mostly took my advanced classes on contemporary women’s radical poetics. I was trying to console my female students—there were a couple of males in that class and they were with us entirely in grief—while I felt like hell myself. Here I was surrounded by a group of young MA and MFA students in their 20s and 30s, mostly women—and what did the future look like for them under this Trump presidency? The students all looked so forlorn, depressed, deeply disturbed. One was openly crying, tears running down her young smooth-skinned face. I, too was feeling that downcast expression wired into my age lines, knowing somehow we had turned a curve and had hit a rock. We crashed. It would be weeks if not months before many of us felt functional again, particularly those of us women who had listened to Trump’s inadvertent talk on the Access Hollywood tape, bragging about himself “grabbing them… by the pussy.” At any any other time in modern U.S. political history, that tape released and circulated by the media would have been the end of his bid for president. Just a photo of a man sitting on a woman’s lap (not a wife) was enough to do in former presidential candidates. But not Trump. It wasn’t enough to stop his bulldozer of bias and tyranny. Yet this election was a sign of worse things to come.

To think that after Joe Biden restored the wreckage left behind by Trump I, winning the election in 2020 hands down—to establish policies following scientific protocol in battling the Covid-19 epidemic and not suggest we inject bottles of bleach; to propos and pass major legislation to actually rebuild American infrastructures not tear them down (as the current president tears down an entire wing of the White House today); to follow Civil Rights laws and mandates to protect women, people of color and the gay community; to encourage across-the-aisle negotiations—and only to be ousted by rumors of age-related mental disintegration (one terrible Biden speech did not help). And then to see the presidency lost again to a man with worse mental health issues certainly than Biden may have ever had. Trump of course won against our brilliant but under-celebrated Black-Asian woman vice-president, who in her approximately 100 days of campaigning efforts managed to make clear, informed, articulate statements to the American public and warned against a second Trump presidency. To think she lost (and now is being blamed for that loss—and her book about it panned by critics). She made a bid for the highest office in the land, of a racist-sexist nation. And we all lost.

And what did we lose when Trump won again?

Who read Snyder’s little book and reflected upon its concerns and contents?

To have Trump win again in 2024—this time winning the full popular vote, after being convicted of a felony in criminal court, after losing a civil suit for raping a female writer in a Bergdorf Goodman dressing room and then (repeatedly) defaming her—what does that mean about American society?

To have Trump win again while the man was under Special U.S. Counsel Jack Smith’s active prosecution for well-documented attempts to overturn the 2020 election and obstruct the transfer of power to Biden—what does that mean, about “us”?

And then to watch Trump himself “pardon” and release all members of the January 6 mob that stormed the Capital, those who endangering many lives and cost the lives of several: hooligans pardoned for serious crimes of violence and treason the very day he took a seat again in Oval Office—.

What does this all mean? And why are we now a nation committed to Trump’s tyranny?

I’m not sure I have answers, but it appears that

American feminism as a movement maligned by men and women alike is now dead, or nearly so in this era. (And women have officially lost the right to control their own reproductive bodies in much of the country, imperiling their heath and sometimes lives);

racism continues to be an overt, highly active belief system that informs our political economy as well as society as well as the economy, whose serious threat is ignored even sometimes by racially oppressed groups themselves—as we saw in the swell of Latina/o support for Trump in the last election;

not enough citizens have read Tim Snyder’s fascism-advice handbook—even if it is free online;

not enough citizens read, and that American education is in the mud.

Going back to Synder, who since writing On Tyranny moved out of the country with his wife, Marci Shore (also a scholar of fascism with an emphasis on Russian totalitarianism)—they now live over the border in Canada. They teach now, not at Yale, but at the University of Toronto.

They created a video op-ed for the New york Times, published last May, explaining why they were leaving the United States. They explain in the video-opinion piece that they know the signs of tyranny, that it was no longer safe for them as scholars of fascism to do their work and live in this country.

Here they explain in their poignant video— with their former Yale colleague in philosophy, Professor Jacob Stanley, who went along to the U of Toronto with them—what the signs are, and why they no longer feel safe:

As the video script narrates, they watched as immigrants lacking elements of residential paperwork were being pulled off the streets, or in immigration courts where they were trying to resolve paperwork, or in schools and businesses and even in their own homes, by masked men (ICE agents). They were then sent to detention centers, and put on planes and flown to countries not of their origin, to be confined under foreign dictatorships paid to keep them incarcerated under slave-like conditions—all without trials or legal counsel.

They watched as students, too, on official U.S. student immigration visas, were apprehended while walking near their apartments and taken into custody, then incarcerated for perhaps a long time, for writing an op-ed in a student newspaper defending Palestinian rights.

Are things as bad as they say?

I think they’ve gotten worse.

*

Let us recall Synder’s important Lesson No. 1 from On Tyranny. It begins:

Do not obey in advance.

And yet “obeying in advance” is exactly what most if not all U.S. institutions and the people in charge of them have done under the second Trump administration.

After attacks by the Trump administration against American universities—like Columbia but countless others—with the faux excuse of anti-semitism, and the withdrawal of federal funding for research central to many university’s survival, universities began disciplining students supporting the Palestinian cause by expelling them or holding records, even firing some Palestinian-supporting professors (mostly with unsecured jobs but even a few tenured professors took such blows). Suddenly, the Right of Free Speech did not exist on university campuses.

Then, threatened by Trump with severing their federal contracts and punishing law firms for representing clients this president does not like, or who do not favor his policies, several of America’s biggest, most prestious law offices bowed down before Trump, agreeing to spend about 1 billion dollars in pro-bono work to support MAGA causes. (Many small firms and independent litigators opposed this action by Trump by filing some 400 lawsuits against the Administration; not the big guys.)

And even before Trump was re-elected, media outlets —including the once revered Washington Post, now under Amazon-Bezo’s corporate ownership—genuflected before Trump, refusing to endorse the only viable, sane and reasonable candidate for President in the 2024 election, Kamala Harris. Instead, the Editorial Board was not allowed to endorse a candidate. This lack of endorsement broke history as Wa-Po has endorsed a candidate for decades. In general, the corporate media has shifted to the right of center in order to accommodate the cowardly new world fashioned by Trump and company. MSNBC fired Medhi Hassan and Joy Reid, renaming itself MS Now for some reason. CNN seems to have avoided topics that might cause conflict with the president entirely; it’s like eating milk toast to watch CNN coverage of news stories. The New York Times, while occasionally offering stories critical of Trump, strides a high-wire act of attempted non-confrontation with him, such as regularly portraying the concerns of Republican voters as if shared widely across the country—even though the truth is that Trump’s poll numbers continue to spiral downward into the gutter. He is now the most unpopular president in polling history.

Thanks to voters, the Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United decision to let campaign finance spending go unchecked, and a certain amount of gerrymandering, the U.S. Congress is right now completely beholden to Trump, just as seem to be these other institutions of power. The speaker of the House, conservative Republican Mike Johnson of Louisiana, is a true minion for the president. Anti-democratic practices, like keeping the House out of session for 54 days to prevent negotiation about the recent federal government shutdown, and to prevent newly elected Arizona 7th district Democratic Representative Adelita Grijalva from taking the oath of office because she was going to vote yes on releasing the Epstein files, which might embarrass the president (once Epstein’s best friend) are typical acts of this House speaker in his efforts to assuage and pamper Trump, grant his every wish, and allow the president to control Congress through Johnson, the Trump robot simulacrum.

And thanks to Trump’s appointment of Elon Musk earlier this year to a fake federal “agency” that called itself “DOGE,” the federal government is in shambles. The federal government can no longer operate as an institution upholding American protections, services and rights, after being stripped and denuded of vast numbers of employees, particularly individuals perhaps not entirely Trump-friendly.

And so, too, the U.S. military has been stripped of its “JAG” lawyers at the Pentagon, whose job it was to keep the U.S. military in line with the law. The military brass is also being fired and whittled down as we write to become a cohort of Trump-supporters. So the military, too, “obeys in advance,” at least it has to now, and even no longer active-duty military officers like Mark Kelley (Democrat of Arizona), who have dared to question a president’s right to deploy troops to police American cities and have asked American troops to follow the law, is being threatened with court martial.

We are now beyond the moment in which American institutions, at least, could NOT “obey in advance.” The Rubicon seems to be on the far side now, in back of us, disappearing into our hindsight. Synder’s second “lesson” in On Tyranny is “defend institutions.” We seem to have moved past that possibility, too. The institutions are quickly becoming corroded, useless against fascism.

And did law firms like the powerful Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison “remember professional ethics” (Snyder’s Lesson No. 5) when kowtowing to Trump’s threats to cut their federal contracts if they did not stop defending his potential political enemies. They just up and offered to pay a big bill to support Trumpian causes in free pro-bono legal help.

And in allowing U.S. troops—hired and trained for foreign combat—to be used to control US civic streets (so far in L.A., Chicago, and D.C.), haven’t we also failed to heed another Synder warning, Lesson No. 6, to be “wary of paramilitaries”?

*

In this issue of CDLS, most of us have read a lot of history and we have read Snyder. We have also read others on fascism and tyranny, like the great Hannah Arendt, who wrote prolifically on totalitarianism, anti-semitism, and political violence.

And while perhaps we can no longer heed Synder’s advice on combatting many elemental aspects of fascism, many of us writers and artists represented in this issue are also professors and teachers who can teach students, at least, to think about what is happening. And we can “be kind to our language,” as Synder suggests in his Lesson No. 9, by writing with diligence, passion, and researched information on this topic. We can cultivate through the power of our literary words what is true, and counter what is “false news” or lies.

As Synder tells us in Lesson No. 9, we need to “believe in truth,” not misrepresentations of facts and uses of false logic. We need to call it out when lies are perpetrated and circulated.

Furthermore, as scholars, teachers and artists, we can “investigate” (Lesson No. 11). We can use our informed reading and analytical skills to dig up and digest information, and to share what we discover. We can delve deeply into issues and understand the motivations and reasons behind Trump’s wiles and fantasies. We can analyze his MAGA support base and try to shed light through the dissemination of accurate, fact-based information. Thus, we can fight against the corruption of so many fallen agencies under Trump, like the new CDC under Robert Kennedy Jr.’s terrible management, which is currently spreading lies about supposed “side effects” of truly life-saving vaccines for children.

We also become experts in “listen[ing] for dangerous words” (Snyder’s Lesson No. 17). We can lead the way—as professionals and artists rooted in the use of our languages—to question the use of “dangerous words,” to write and teach and make art against their foul intentions.

We can use the radical language of poetry—a language engaged with the power of linguistic uncertainly, the contradictions in any semantic “meaning,” and the questioning of an ego-based identity for the subject—to make new “words’ that supplant the fascist take-over and control of language, which Scappettone writes about in her just-released book study, Poetry after Barbarism: The Invention of Motherless Tongues and Resistance to Fascism (Columbia UP).

Through the openings available in poetic language, human intelligence and its need for political freedom are reborn again and again, in our uses of words themselves.

*

In short, we can all (Snyder’s Lesson No. 8):

“Stand out.”

The writers and artists published in Issue 5 have thus done so. By writing and publishing our critiques and ironic observations of, our out-right funny satires about, our current fascist-leaning U.S. leadership, we stand out. And we stand our ground for U.S. democracy. We write of the seriousness of the situation, watching our nation fall under the totalitarian disease. We also revel in the ridiculousness of Trumpism, the short-sighedness and opera buffa that is the man himself. We stand out with our visual as well as verbal languages that signify thinking, not obliterating thought. As Arendt wrote in her 1970 essay, “On Violence,” on the topic of the perpetrators of authoritanian violence:

The trouble is not that they are cold-blooded enough to “think the unthinkable,” but that they do not think.

In this issue, we think. And think again.

Letters & Chants is a new feature of CDLS Journal, where we publish readers’ responses. If you wish to comment on this issue, you can write or send media materials to us at:

chantdelasirenesubmissions@gmail.com